I don’t know what to call this besides illogical:

- The cost of a college education has been increasing more each year than the cost of living has.

- Wages, particularly in the last few years, have not been keeping up with the increasing cost of living.

- Therefore wages are falling way behind tuition inflation.

- A college degree is becoming more essential to employment every decade, but the process of earning it seems to be teaching graduates less and less applicable knowledge.

- A rule of thumb generally preached to prospective college students who need student loans is that they should borrow a total of no more than their annual starting salary after graduation.

- So many college freshmen don’t actually know what they’ll be doing after graduation. But architecture students do.

- So many college students have no idea how much they’ll be making after graduation. But architecture students can find this out pretty easily.

- The 2013 AIA Compensation Report came out last month. Click here for an article about it, that includes some of the data.

What do entry-level architecture graduates make? I’m going to spell out some of that data from the report.

- Nationwide, mean (average) compensation for an “Intern 1” position is $40,000. (“Intern 1” is a person who has graduated from architecture school, works full-time in an architecture firm, and is on the path towards licensure.)

- Compensation for these new grads a little higher in some places. (In the Mid Atlantic Region it’s $41,800.)

- And it’s a lot lower in some places. (In the East South Central Region, it’s $34,800.)

- Remember – these numbers are just averages.

- According to the rule of thumb, architecture students should borrow a total of no more than $40,000 in student loans, since they’re likely to make no more than $40,000 in their first year after school.

So, as I wrote on a forum recently, if you have to borrow money to go to school, keep these things in mind:

- To get a professional degree (a BArch or an MArch) in architecture, school takes 5 or 6 years.

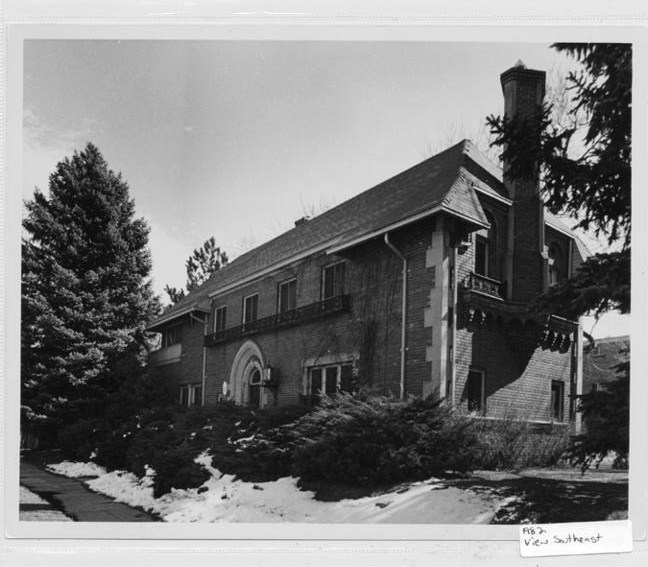

- My alma mater’s current tuition is over $44,000 per year, not including room and board. My alma mater has a 5-year professional degree (a BArch).

- Tuition alone for the state university in my state is over $10,000 per year, and you’d have to go for a total of 6 years to get a professional degree (4-year degree plus a 2-year MArch).

- In most states, you need a professional degree if you want to be able to pursue licensure.

- A growing number of architecture firms won’t even hire you unless you have a professional degree. (According to the AIA report referenced above, 20 percent of firms do not hire employees without a professional degree in architecture, up from 15 percent in 2011.)

- You might need to borrow money for room and board, or for living expenses, in addition to tuition. If, while in school, you have a job, or live with parents or a spouse who supports you and pays for living expenses, and you get in-state tuition in my state, you’ll likely borrow something like $60,000.

- If you go to my alma mater, don’t have a job, live on campus, and borrow money for tuition, room and board, you might need something like $285,000, unless you get “gift aid” from the university, in which case you might be borrowing “only” $142,000.

- You’d never make $142,000 in your field as an architecture grad in the first few years after school.

- In fact, that figure is close to the mean of what architects top out at right now.

- The mean salary for CEOs of architecture firms in New England (the highest-paid region in the country for architecture CEOs) is $151,500. That is the highest number on the whole survey.

- And nobody gets to that compensation level very fast – the mean compensation for “Intern 3” is $49,200. (“Intern 3” is a person who has graduated from architecture school, has three to six years experience, works full-time in an architecture firm, and is working towards licensure.)

If you have to borrow money to go to architecture school, the math just doesn’t work out.

- Check it out for yourself – figure out how much tuition and room and board and fees and books and supplies cost at the schools you’re looking at. Then figure out what you might make in each of your first few years in an architecture firm in the city you want to be in. (To do this, go to the local AIA office and ask to look at the latest compensation survey results for that city. Do not search online for “architect salary;” the internet thinks you mean “software architect,” or some other IT field, and they make more. ) Then use an online calculator to see if it’ll work. Here’s one.

Something’s gotta give. So what can be changed? I have some thoughts that will be in part two, later this week.